Drones add new perspective to geomatics

Geomatics is an applied science with its roots in traditional land surveying. With the advent of technology such as global positioning systems, three-dimensional laser scanning and geographic information systems, it was renamed in the 1990s. But, if a recent drone-based survey of UCT is anything to go by, geomatics is set to take off once more, writes Penny Haw.

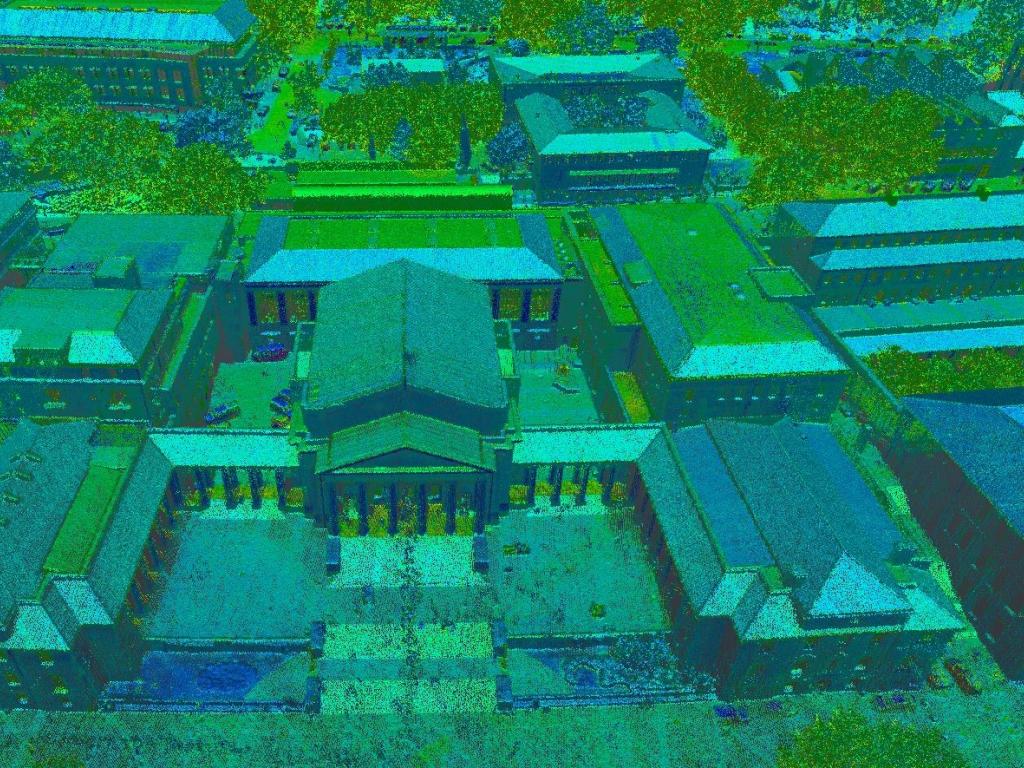

Undertaken on a calm August morning, the University of Cape Town (UCT) Geomatics Division’s survey of the institution’s upper campus, using drone-based light detection and ranging (lidar) and aerial imagery, is unprecedented.

Airborne laser scanning from a large drone equipped with specialised equipment.

Not only were the equipment and techniques used (supplied by Cape Town-based measurement solutions specialist, Horts Geo-Solutions) among the most sophisticated of their kind available worldwide, but the data was captured faster, more accurately, and in more detail than that provided by pre-existing surveys of the area. Among other things, the data will be incorporated into the department’s on-going scanning and mapping of the campus, which is built on by fourth year students every year.

Moreover, the drone survey added to the department’s knowledge of the advantages and challenges of surveying using drones.

“The exercise gave us an excellent demonstration of the legal and safety issues required by such work,” says the department’s chief technical officer, Mignon Wells. “We also saw what precision is required by pilots who, on the day, had to navigate airborne dangers by way of large raptors and multiple flyovers by helicopters, with whom the pilots need to maintain radio contact.”

The drone survey also provided the Geomatics Division with an opportunity to draw attention to the diverse and evolving world of geomatics.

Dancing with drones

Strict and cumbersome legislation regarding the commercial flying of drones in South Africa notwithstanding, the value of using the machines to collect spatial and geographic data in digital form is increasingly acknowledged. It’s not just that the unmanned vehicles help save time, are less environmentally disruptive than other technologies, and can go just about anywhere and fill important gaps inaccessible to manned aircraft and ground surveyors, it’s also that drone technology is helping expedite associated geomatics technology. And this technology, in turn, is helping produce more informative images.

The drone itself does not produce images. This is done by navigational systems, scanners, mapping systems and cameras carried by the machine. Undertaking drone-based surveys and scans right require a licensed drone pilot and (unless the pilot is also a qualified surveyor) a professional geomatics practitioner.

UCT upper campus lidar sample curtsey of A/Professor Julian Smit.

But, explains UCT Geomatics Associate Professor, Dr Jennifer Whittal, it’s what happens and what is done with the data collected that affirms the value of geomatics. And, where geomaticians recognise innovative ways of collecting, analysing, manipulating and presenting data because of new opportunities provided by drones, the value proposition grows. This is one of the reasons companies like Horts Geo-Solutions like to work with universities.

“Our principals (Horts Geo-Solutions represents European brands Zoller + Fröhlich (Z+F), RIEGL, DotProduct, LFM, Pointsense and ClearEdge 3D) are always eager to hear what the UCT Geomatics Division is working on,” says Horts Geo-Solutions CEO, Francois Stroh. “It’s the work done in places like this that help advance technology and systems.”

The application of drones in geomatics began with land surveying, site mapping, volumetric measurement and inspections (including environmental studies), and damage assessment, but is evolving as quickly as geomaticians and developers are creating new methods and technology. Drones are particularly useful in damage assessment in mines, says Stroh, where time is crucial. They are also used by mines for stockpile inspections, environmental management, road monitoring and to plan blasting work. In fact, by disrupting the data gathering industry for the better, drones are adding to the already diverse application of geomatics across numerous industries.

Surveying is just the start

Although, when students sign up to study for a BSc in Geomatics, the initial years cover all the basics of surveying, the four-year qualification equips them for a great deal more than pulling on large hats and spending their days outdoors traipsing around the countryside with various pieces of equipment.

Geomaticians focus on concepts like smart cities and smart agriculture. They are found working offshore for minerals and oil companies. Others, with expertise in remote sensing or photogrammetry (making spatial measurements from photographs), work for environmental or national heritage organisations. The UCT Zamani Project, for example, creates metrically accurate digital representations of largely African historical sites, including Swahili sites and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Route in East Africa.

Moreover, geomatics plays fundamental role in the development of self-driving cars; without geomatics technology, such as global navigation satellite systems, three-dimensional maps and lidar, autonomous driving won’t be viable. Geomaticians also find employment in companies that work on projects that use spatial data to solve real world issues. For example, spatial data is used to develop innovative mobile mapping products that we use every day in applications such as Google Maps and Uber. Even the entertainment industry calls for the services of geomaticians in cases, for example, where movies require the virtual sets.

A recent global study found that, driven by the growing range of industries and applications, the geomatics industry is growing at nearly 35% annually. Curiously though, despite the many diverse opportunities in geomatics and the dynamic role it plays in innovation, the field is relatively low-key.

“In many instances, our work is rarely highlighted to the general public,” says the UCT Geomatics Division’s Kaveer Singh. “This is unfortunate because society does not get to see the important role geomatics plays across multiple industries and in their daily lives.”

While geomatics draws heavily from the sciences of mathematics, physics, and computing, its basis is in geography and applications extend to archaeology, geology, environmental science, geodesy, agriculture and even, particularly in places like South Africa where issues of land tenure reform are important, sociology.

“Historically, geomatics was positioned as a career that suited practical individuals with backgrounds in mathematics who like detail and enjoy the outdoors,” says UCT Geomatics Associate Professor, Dr Julian Smit. “But, with the scope of opportunity having evolved – expedited by technology, including drones – this has changed. These days, there are plenty of opportunities for geomaticians who don’t like the outdoors and prefer to do important work at their desks. BSc in Geomatics opens doors to a growing number of career options in a variety of industries and fields.”

For more information on BSc in Geomatics, go to http://www.geomatics.uct.ac.za/

Atricle written by Penny Haw